Thank goodness Cassandra came back as the BDC's full-time Library specialist in January 2024. Since then, we've been working on ticking off some of my "hope to do before retirement checklist" items. Back in October 2022, I made a post on the BDC's Facebook page about the "Poisoned Book Project" at Winterthur Library. Even though the project sounds more like a murder mystery title than a preservation issue, it added this to my pre-retirement to do list: "Eyeball the clothbound books in the BDC for green 19th century bindings. If found, devise a preservation and safety handling plan." And thus was born the roots of Cassi's latest blog post in honor of the Summer Reading Programs 2025 theme of "Color our World." The post goes beyond Arsenic Green books to include lead chromate or chrome yellow books, too. Enjoy! -- gmc

|

| Sidewall (possibly France); paper with applied ground color, unprinted; 25.5 x 22 cm (10 1/16 x 8 11/16 in.); Gift of Grace Lincoln Temple; 1942-19-16. From the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. |

If you've ever seen Dr. Suzannah Lipscomb's documentary, "Hidden Killers of the Victorian Home," you'd know that our ancestors were exposed to a medley of toxic materials and products while going about their day-to-day lives - things that we now steer far clear of. One of the most popular substances was arsenic. Arsenic could be found in its usual, expected applications, like in rat poison, as well as in other, more dangerous everyday places like paints, clothing, and sometimes even food. That's because arsenic was being used to create beautiful, vibrant emerald greens that outshined other pigments on the market. Manufactured pigments like Scheele's and Paris Green became widespread in Europe, the UK, and the US and were used in house paint, textile dyes, wallpapers, and occasionally as food dyes, with little care to the serious threat these colors posed to human's health. In the world of libraries and archives, we are extra cautious of green books from the mid-1800s, as these may contain arsenic green pigments. Here at the BDC, we wanted to take a closer look at arsenic green as part of BCL's "Color Our World" Summer Reading Program, examining the ways this deadly color relates to our collection both as a pesticide and as a pigment!

|

| Macdonald, Wilkins & Co. advertisement for insecticides, including Paris Green. From the May 12, 1938 issue of the Beaufort Gazette, available on microfilm in the BDC. |

Paris Green was also applied more broadly across swathes of land and water as an insecticide, particularly for mosquito control in the early to mid-1900s. In the 1920s, Paris Green was tested in salt marshes of Mississippi for effectiveness in eradicating mosquito larva, with the hope that it could be used in other Southern marshes. The scientists mixed Paris Green with sand and scattered it along the surface of small bodies of water containing mosquito larva, coming back later to count the number of larvae still alive. The scientists found that the arsenic was effective at killing the larva. Also, the sand mixed with the Paris Green would sink to the bottom of the body of water, and when tested later would often still have arsenic bonded to it. This allowed the arsenic to be more effective for a longer period of time in comparison with Paris Green just dusted along the surface of the water. I could not find specific information to confirm that Paris Green was used in salt marshes locally but, given that the use of Paris Green to kill mosquito larva in standing water continued through World War II throughout the US and abroad, it is very possible. More research would be needed to confirm if and where Paris Green was used for mosquito-control purposes in the Lowcountry.

|

| Dust Paris green on swamps and ponds; circa 1941–1945. From Record Group 44: Records of the Office of Government Reports, World War II Posters series, National Archives and Records Administration. |

Paris Green and Scheele's Green were also used as pigments, as they created a bright and beautiful emerald shade. According to an article on arsenic dyes by Lidia Plaza, arsenic pigments were much easier to work with and more long-lasting than other green pigments on the market at the time, thus leading to their more common use despite concerns over negative health impacts. As long as the "dose" was low, the Victorians believed that the poisonous substance would not cause any damage to their health, so dresses were dyed in arsenic green, wallpaper was made with arsenic green pigments, and even book cloths for the covers of popular novels were coated in arsenic green.

However, concerns about the safety of arsenic green began to grow. In 1874, a book entitled Shadows from the walls of death by R.C. Kedzie of the Michigan State Board of Health was published which condemned the use of arsenical wallpapers and included more than a hundred samples of such poisonous wall coverings. Kedzie found and documented in his book cases of children growing ill in rooms with arsenic green wallpaper, where the pigment slowly dislodged and turned into dust which was breathed in by the children. Removal of the wallpaper cured the children of their sickness, and Kedzie set about promoting the removal of all arsenic wallpapers for the safety of families. Per an Atlas Obscura article, Kedzie sent copies of this book to public libraries throughout Michigan in an effort to educate and warn the public to the dangers of arsenic green wallpapers. Kedzie's book is now one of many which contain arsenic green.

Archivists are more familiar with this application of arsenic green, as a pigment, as it can now be found in historic materials like books, prints, and even wallpaper samples (thanks to Kedzie's Shadows...) that we may carry in our collections. As I said, arsenic green's emerald hue was a popular color, so it was applied to book covers or painted in illustrated editions somewhat frequently during the mid-to-late 1800s. The issue of arsenic-laced books was brought to the attention of archival professionals thanks to the recent efforts of the University of Delaware's Poison Book Project.

In an article written on the Poison Book Project, UD professor and conservator Melissa Tedone said that the project began when she recognized the shade of arsenic green wallpaper as being the same shade of green as a book cover in her lab. Working with her fellow colleagues, including some with the UD's College of Agriculture, she confirmed her suspicions that the book cover contained arsenic through lab testing, and proceeded to test more books in their collection that were bedecked in the same emerald color. Through doing this work, Tedone and her colleagues have created a database of arsenical books and a website which explains their work and the identification process to other archival professionals.

|

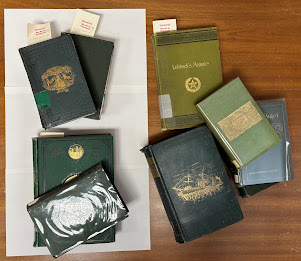

| A selection of green books from the BDC Stacks |

|

| The Poison Book Project's Do You Have a Poison Book? Flowchart |

That seemed all well and good - I could finally take a deep breath without fear of breathing in arsenic dust! - until I paid closer attention to the right-side of the Flowchart. Answering "No" to the question "Is your book green?" led to a lengthy answer cautioning that, while your book likely was not arsenical, many books from the 19th century, no matter the color, contained the less-poisonous-but-still-toxic lead chromate. Lead chromate (AKA chrome yellow pigment) was often used to tint book cloths a bright, golden yellow or combined with other pigments (like arsenic green) to create a variety of shades of green, red, blue, and more. The Poison Book Project even stated that "Nearly 50% of the nineteenth-century (1800s), cloth-case bindings analyzed for the project to date contain lead in the bookcloth, regardless of color."

Yikes.

So, what's the remedy? Thankfully, chrome yellow does not decay in the same way as arsenic green, so current testing by the Poison Book Project has shown that it is unlikely to transfer to users through handling. However, out of an abundance of caution, the BDC will be limiting the handling of our 19th century books and encourage patrons who do handle the materials to take extra caution not to ingest anything from the book covers, following the University of Delaware's Poison Book Project handling tips and the steps the University of Illinois has taken. If digital versions of the books in question are available online via Archive.org or Hathitrust, we will use those editions as access copies instead of the physical versions. We are also looking into the option of placing the books in additional protective covers or boxing the items entirely separately. In the interim, we have flagged the titles I identified in this exercise with special cautionary bookmarks, and plan to go through our inventory and add them to other books from the 19th century. This is a new issue in the field of archives and preservation, and we will react accordingly as more research comes out.

No comments:

Post a Comment